In Appendix A to her second book, College Writing and Beyond (2007), Anne Beaufort worked to improve learning outcomes, “including positive transfer of learning for an academic writing class.” But five years later, after further reading, reflection, and observation of her students’ difficulties, she recognizes the need to give students “a stronger skill base in academic writing and to foster more positive transfer of learning from writing courses to other contexts for writing” as she articulates in her article, “College Writing and Beyond: Five Years Later” (2012). Here, she revisits her sample course outline and previous suggestions, acknowledges the problems she sees with the pedagogy and curriculum she previously set forth, and explains what she is now experimenting with as she continues to teach college writing.

In Appendix A to her second book, College Writing and Beyond (2007), Anne Beaufort worked to improve learning outcomes, “including positive transfer of learning for an academic writing class.” But five years later, after further reading, reflection, and observation of her students’ difficulties, she recognizes the need to give students “a stronger skill base in academic writing and to foster more positive transfer of learning from writing courses to other contexts for writing” as she articulates in her article, “College Writing and Beyond: Five Years Later” (2012). Here, she revisits her sample course outline and previous suggestions, acknowledges the problems she sees with the pedagogy and curriculum she previously set forth, and explains what she is now experimenting with as she continues to teach college writing.

Beaufort highlights four considerations for improvement to her previously proposed curriculum:

- Clarifying assumptions about learning goals in writing courses

- The issue of guideline for course theme(s) and the relationship to teaching for transfer

- Applying principles of transfer of learning explicitly to the pedagogy associated with associated with any writing tasks in any instructional setting

- The ideal types and number of genres in academic writing classes with pragmatic aims

When discussing her first consideration, Beaufort acknowledges that “the major writing projects proposed in Appendix A are not the best for helping students gain analytic skills and rhetorical skills in typical academic genres. Students are asked to write in too many genres in a single writing course and in genres that are not widely used in a lot of other academic disciplines.”

When discussing the second consideration, she identifies her proposal in Appendix A to utilize a course theme, “Writing as Social Practice.” Beaufort’s concern here is not with the proposed theme, however—it is the limitation she implicitly set on potential themes: What I did not say as clearly as I would like to now is that this is only one possible course theme that would encourage in-depth intellectual exploration into subjects from any number of discourse communities.” Further, Beaufort notes that “Writing as Social Practice” as a theme “would enable writers to become more self-aware [but she] conflated that goal with the goal of teaching for transfer. Teaching for transfer can be accomplished, if appropriate strategies are used, no matter what the course’s subject matter.”

For the third consideration, Beaufort expresses her concern for the little explicit instruction given to writing teachers that is needed to teach students to understand and apply key concepts to writing tasks (discourse community, genre, rhetorical context, etc.). She notes that “[t]asks must be framed appropriately and repeatedly in order for writers to carry forward those big concepts to help them analyze and successfully accomplish writing tasks in other situations.” Also, helping students to understand and apply genre theory should become a standard practice in composition pedagogy, which was not previously made clear in Appendix A.

For the fourth consideration, Beaufort submits, “I did not think through carefully enough whether the particular genres I suggested for writing assignments in Appendix A would be most efficacious for teaching core academic writing skills.” She explains that she has removed her previous assignments from the syllabus (literacy autobiography, genre analysis, and ethnography assignment) and replaced them with two major assignments: a rhetorical analysis of a nonfiction text and a literature review of a body of research that seeks to address an important question.

Beaufort’s revisions cause me to reflect on my own pedagogy and curriculum design for first-year composition. I appreciate her honesty and candidness, and question to what extent I am encouraging students to compose in genres that will be meaningless to them once they have completed FYC. Or, is the integration of genre awareness as a threshold concept in my curriculum useful regardless of the genres students actually compose?

Beaufort, A. (2012). College writing and beyond: Five years later. Composition Forum 26. Retrieved from http://compositionforum.com/issue/26/college-writing-beyond.php.

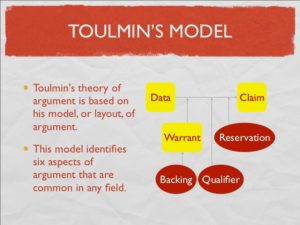

The authors note that the evidence from their study suggests that the majority of the twelve students improved their ability to articulate claims and support them with evidence in FYC. In the WAC courses, the authors found that “[w]hile the students in this study encountered in WAC a diverse variety of genres, most of those genres required them to support claims with evidence. In this regard, students appeared to benefit from related instruction in FYC. That is to say, students’ development of ability to articulate and support claims in FYC appeared directly related to their ability to do so in their later WAC courses” (p. 46). But after reading this article, I have several questions for the authors about their

The authors note that the evidence from their study suggests that the majority of the twelve students improved their ability to articulate claims and support them with evidence in FYC. In the WAC courses, the authors found that “[w]hile the students in this study encountered in WAC a diverse variety of genres, most of those genres required them to support claims with evidence. In this regard, students appeared to benefit from related instruction in FYC. That is to say, students’ development of ability to articulate and support claims in FYC appeared directly related to their ability to do so in their later WAC courses” (p. 46). But after reading this article, I have several questions for the authors about their

Condon’s and Rutz’s assertion begs a major question in the field: Does goal-oriented progress, or the use of outcomes, increase the tension that exists between the disciplines?

Condon’s and Rutz’s assertion begs a major question in the field: Does goal-oriented progress, or the use of outcomes, increase the tension that exists between the disciplines?  analytical to a rhetoric and writing studies (RWS) course with a writing about writing (WAW) approach. Interestingly, Ruecker acknowledges that though he says he uses a WAW approach, he finds it to be too broad a title for what he does within his course, in which he seeks to expose students to disciplinary discourses (89). Ruecker further explains that describing his course as using a writing about writing approach is problematic because it ignores rhetoric. Though, because he focuses on writing as a subject, he finds it to be the most suitable title to explain what he does.

analytical to a rhetoric and writing studies (RWS) course with a writing about writing (WAW) approach. Interestingly, Ruecker acknowledges that though he says he uses a WAW approach, he finds it to be too broad a title for what he does within his course, in which he seeks to expose students to disciplinary discourses (89). Ruecker further explains that describing his course as using a writing about writing approach is problematic because it ignores rhetoric. Though, because he focuses on writing as a subject, he finds it to be the most suitable title to explain what he does. is director’s initiative to “design courses more in line with RWS” (88). These questions are difficult to answer as Ruecker’s justification for his course redesign choices are unclear. Yet, on the last page of his article, Ruecker suggests that the goal of a FYC course is to challenge students “with intellectually demanding disciplinary content, material that better prepares students to write across a variety of academic and social contexts” (98). He seems to be speaking to writing across the curriculum (WAC) as a means to achieve transfer

is director’s initiative to “design courses more in line with RWS” (88). These questions are difficult to answer as Ruecker’s justification for his course redesign choices are unclear. Yet, on the last page of his article, Ruecker suggests that the goal of a FYC course is to challenge students “with intellectually demanding disciplinary content, material that better prepares students to write across a variety of academic and social contexts” (98). He seems to be speaking to writing across the curriculum (WAC) as a means to achieve transfer

In her article, “They Can Get There from Here: Teaching for Transfer through a ‘Writing about Writing’ Course,” Jennifer Wells explores her justification for and experience with teaching a high school composition course using a writing about writing (WAW) approach. Though much of my personal research focuses on first-year composition (FYC), Wells’ interests and mine intersect where Wells seeks to prepare her senior English students for unknown college writing contexts, including FYC. She understands that, as writing teachers, we are not experts in writing in the disciplines, but we can prepare our students for writing in the disciplines by cultivating an awareness within them that prepares them to write in a variety of contexts.

In her article, “They Can Get There from Here: Teaching for Transfer through a ‘Writing about Writing’ Course,” Jennifer Wells explores her justification for and experience with teaching a high school composition course using a writing about writing (WAW) approach. Though much of my personal research focuses on first-year composition (FYC), Wells’ interests and mine intersect where Wells seeks to prepare her senior English students for unknown college writing contexts, including FYC. She understands that, as writing teachers, we are not experts in writing in the disciplines, but we can prepare our students for writing in the disciplines by cultivating an awareness within them that prepares them to write in a variety of contexts. In this new curriculum, Wells is intentional to include opportunities that promote what Perkins and Salomon call “mindful abstraction,” or guiding students “to deliberately search for connections” (qtd. in Wells 57). Her curriculum is shaped around three units in which her students 1.) question, research, and define others’ definitions of “good writing,” 2.) explore potential discourse communities they will enter once in college, and 3.) research writing in their intended major in the writing in the disciplines unit. As students move from unit to unit, Wells prompts them to self-reflect on their writing discoveries. Though, she does not detail the specifics of how she manages this self-reflection activities.

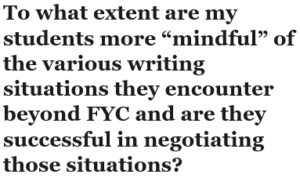

In this new curriculum, Wells is intentional to include opportunities that promote what Perkins and Salomon call “mindful abstraction,” or guiding students “to deliberately search for connections” (qtd. in Wells 57). Her curriculum is shaped around three units in which her students 1.) question, research, and define others’ definitions of “good writing,” 2.) explore potential discourse communities they will enter once in college, and 3.) research writing in their intended major in the writing in the disciplines unit. As students move from unit to unit, Wells prompts them to self-reflect on their writing discoveries. Though, she does not detail the specifics of how she manages this self-reflection activities. s article was written in 2011, Wells was not yet sure how successful her writing about writing pilot had been. She explains that “questions still remain” and she would find out at her former students’ homecoming how they felt about college writing and their preparedness for it. But herein lies another intersection between Wells and I, as I too often wonder about the short-term and long-term effectivity of the writing about writing approach utilized in my classroom. To what extent are my students more “mindful” of the various writing situations they encounter beyond FYC and are they successful in negotiating those situations?

s article was written in 2011, Wells was not yet sure how successful her writing about writing pilot had been. She explains that “questions still remain” and she would find out at her former students’ homecoming how they felt about college writing and their preparedness for it. But herein lies another intersection between Wells and I, as I too often wonder about the short-term and long-term effectivity of the writing about writing approach utilized in my classroom. To what extent are my students more “mindful” of the various writing situations they encounter beyond FYC and are they successful in negotiating those situations?