While over 200,000 American troops were fighting abroad in the Vietnam War by the 1970s, American education at home was taking a shift toward science, technology, engineering, and math studies (STEM) in order to better prepare a workforce for post-industrial society. Writing education, as a result, also shifted, seeking to identify pedagogical approaches for getting students to think about the content in their various courses and the interrelatedness of writing between them. According to Kevin Eric DePew, Associate Professor of English at Old Dominion University, Writing Across the Curriculum (WAC) emerged as a product of the 70s and a response to this writing studies need: “Though they weren’t using the acronym STEM yet, you had the sense of making everything very STEM-like, or practical, including writing” (personal communication, October 26, 2016). In a post-industrial society in which services were dependent upon intelligent designers and users of technology, practicality in writing meant that the consumers, or students, would be able to see the usefulness and transferability of their writing skills across contexts.

While over 200,000 American troops were fighting abroad in the Vietnam War by the 1970s, American education at home was taking a shift toward science, technology, engineering, and math studies (STEM) in order to better prepare a workforce for post-industrial society. Writing education, as a result, also shifted, seeking to identify pedagogical approaches for getting students to think about the content in their various courses and the interrelatedness of writing between them. According to Kevin Eric DePew, Associate Professor of English at Old Dominion University, Writing Across the Curriculum (WAC) emerged as a product of the 70s and a response to this writing studies need: “Though they weren’t using the acronym STEM yet, you had the sense of making everything very STEM-like, or practical, including writing” (personal communication, October 26, 2016). In a post-industrial society in which services were dependent upon intelligent designers and users of technology, practicality in writing meant that the consumers, or students, would be able to see the usefulness and transferability of their writing skills across contexts.

WAC was one way to get students to perform better by using writing to get them to think about the course content. Today, linked courses, learning commons, and learning communities are an extension of WAC, and if done well, the literacy students learn in the writing class can be used to think

about the material being learned in classes of other subject matter. At institutions where WAC curriculums are utilized, instructors often talk to each other about ways of building knowledge that complement each other as well as foster the transfer of knowledge and skills.

In the WAC field, different methods are utilized by administration, instructors, and scholars to test whether WAC pedagogy is effective. According to DePew, two of the most common methods are experimental study and case study (personal communication, October 26, 2016). To conduct an experimental study, a pretest is often administered at the beginning of the semester to see what the students have knowledge in. Two classes may be chosen, one of which serves as the variable group and is taught with a WAC pedagogy, and the second of which serves as the control group. At the end of the semester, another test is administered to see how student knowledge of the course material has changed among students throughout the duration of the course for both classes. In contrast, case studies are designed to prompt students to talk about how the writing is shaping their understanding of the content of the discipline. The use of writing to learn exercises in the classroom, for example, prompts students to think through key ideas and concepts, and case studies also allow us to witness student development through such exercises.

It seems that WAC, as a practical field, uses practical methods to determine its effectivity. Interestingly, the theories in the field that are used to generate knowledge are also practical. One common theory  represented in WAC is rhetorical theory, which Bazerman and Russell (1994) discuss in their introduction to Landmark Essays. WAC was evident in the rhetorical traditions of the Ancient Greeks as it is today, and for Bazermen and Russell, there is a long tradition in rhetorical theory to support the reasons we have WAC.

represented in WAC is rhetorical theory, which Bazerman and Russell (1994) discuss in their introduction to Landmark Essays. WAC was evident in the rhetorical traditions of the Ancient Greeks as it is today, and for Bazermen and Russell, there is a long tradition in rhetorical theory to support the reasons we have WAC.

Trends in the field reveal that there has been a movement toward practical writing exercises; English instructors are using writing to help students think about the context of their writing situation. This movement has had more buy-in among faculty, a noteworthy point considering that in the beginning of the WAC movement, there were some scholars who pushed against WAC, advocating for expressivist approaches to FYC. DePew commentated that “[t]he desire among WAC stakeholders—deans, instructors, students, etc.—is to use WAC to build an infrastructure or transfer within the university that is sustainable. . . WAC is a field that works to create partnerships with other disciplines rather than trying to ‘save the disciplines’. Proponents of WAC don’t force people to do WAC. . . it should always be voluntary because in order to get success, one must breed success” (personal communication, October 26, 2016). Debates in the field are therefore old as most support the notion that for students to be effective writers in their STEM classes, they must develop the necessary (and practical) writing skills in their FYC classes.

In spite of its ambitions, common theories, methodologies, and trends, WAC remains to be a challenging pedagogy to assess because WAC looks different at every institution. In assessment, scholars seek to determine what is best practice for their program, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that best practice for one program will be the same for another program, so why is it that while WAC seeks to encourage students to see interdisciplinarity across contexts, WAC is rarely the same across institutions?

References

Bazerman, C., & Russell, D. (Eds.). (1994). Landmark essays on writing across the curriculum. New York, NY: Hermagoras Press.

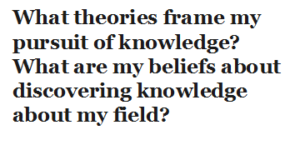

apprehensions about being called “professor” were affirmed when I was tasked with this blog post, and I began to realize the challenge—and value—in being able to articulate how I align myself theoretically and epistemologically. What theories frame my pursuit of knowledge? What are my beliefs about discovering knowledge about my field? Perhaps I have struggled to embrace my position as an educator because I had not before defined myself in these terms, and in doing so, I had not before claimed a position as a scholar in my field or in academia.

apprehensions about being called “professor” were affirmed when I was tasked with this blog post, and I began to realize the challenge—and value—in being able to articulate how I align myself theoretically and epistemologically. What theories frame my pursuit of knowledge? What are my beliefs about discovering knowledge about my field? Perhaps I have struggled to embrace my position as an educator because I had not before defined myself in these terms, and in doing so, I had not before claimed a position as a scholar in my field or in academia.

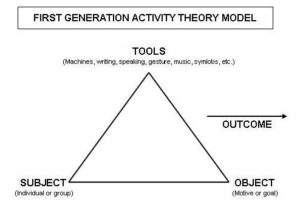

ial opportunities, enable us to use our higher level thoughts in conjunction with our surrounding environments that are working to shape our knowledge and in turn shape our output (e.g. verbal and written speech) (Brufee) (Hewett and Ehmann, 2004, pp. 34-37). Social constructivism allows me to make the teaching and learning experience transparent, which is essential to successful transfer as students leave my English classroom and enter into classrooms of other disciplines.

ial opportunities, enable us to use our higher level thoughts in conjunction with our surrounding environments that are working to shape our knowledge and in turn shape our output (e.g. verbal and written speech) (Brufee) (Hewett and Ehmann, 2004, pp. 34-37). Social constructivism allows me to make the teaching and learning experience transparent, which is essential to successful transfer as students leave my English classroom and enter into classrooms of other disciplines.