Tool Description

FluentU is a learning site (www.fluentu.com) that uses videos to teach users a new language. Nine languages are offered, including Chinese, Spanish, French, English, German, Japanese, Italian, Korean, and Russian. The homepage provides a friendly video that shares an overview of the program. A “Try it Free” link on the homepage takes the user to a page with two 15-day free trial options: Basic and Plus. To sign up for the free trial, the user must provide his or her credit card number. At the end of the 15-day free trial, the user’s credit card will be charged for the selected plan. The Basic plan is $15 a month or $120 a year, and the Plus plan is $30 a month and $240 a year. The Basic plan offers unlimited watching and listening of videos. The Plus plan offers unlimited watching and listening of videos, but it also allows users to download PDF transcripts of each video for study while offline. It also provides quizzes, so users can self-measure their learning.

The tool utilizes YouTube to publish a variety of videos including, movie trailers, singalongs, news, music videos, and inspiring talks, so videos can be streamed but not downloaded. These videos include subtitles in two languages: the language being learned and the user’s native language. This allows users to watch, listen, and read to reinforce content. If the user hovers the cursor over a particular word in the subtitle, the video will pause, and the user can practice the material he or she sees on screen. At this point, the user may opt to review the definition of the word or see it used in other example sentences. The site tracks the learner’s progress and uses this progress to create “personalized” quizzes.

The range of intended audiences for this program is broad. In educational contexts, the site seeks to target K-12, universities, language schools, independent teachers, and home schools. The site also identifies several professional fields as audiences for this program, ranging from aviation and engineering to hospitality and sales. And, a user may choose to utilize this program for individual learning.

Considerations for FluentU

Introducing FluentU into the composition classroom would respond to Matsuda’s (2006) argument that composition has not fully recognized the presence of second language writers in college composition courses (p. 638). Videos that are published in an individual’s native language and integrated into instruction would embrace the language diversity of the classroom and promote the acceptance of those who do not speak or write in fluent English. It provides an opportunity to celebrate rather than ignore the presence of L2 writers in our classrooms.

FluentU as a resource was easy to find with a Google search and easy to learn and use with its simple premise: watch videos. FluentU could supplement instruction in any classroom as a digital instructional tool, and in doing so, support the Conference on College Composition and Communication’s (CCCC) Statement on Second Language Writing and Writers. In this statement, the CCCC addresses the writing teacher’s responsibility to draw on student competencies when designing curricula. They express that many L2 writers may possess strong skills in technology use, and it should therefore be included in the ESL classroom: “second language writers can learn to bridge the strategies they use to communicate socially through digital media to the expectations of the academy.” While FluentU could support the bridge between digital and academic contexts, it alone would not suffice to teach students how to write in academic contexts as the program does not provide opportunities for writing—only listening and reading.

One reviewer, Jesse, shared a mixed review of the program. He identified its ease of use as a selling point, but criticized it for not providing speaking opportunities, lack of scaffolding for the lessons, and the videos are too short, not exceeding 10 minutes. I a response to Jesse, another reviewer commented, “I’ve been trying FluentU. But so far I’ve found it lacking. I’ve purchased a one year subscription and less then [sic] a month in I’m starting to regret it. There are apps on my phone that seems to do the exact same thing this app does with [sic] less charge” (Hannibal Raspberry). While FluentU could be used in a composition classroom, its use would come with a cost to students.

To Adopt or Not to Adopt FluentU

I would not adopt this tool for several reasons. The parent company, FluentFlix Limited, presents their product as a universal language learning software, but one software cannot effectively reach such a broad range of audiences (professional and educational groups and individuals). Perhaps if FluentU offered more individualized programs that were tailored to group and individual instruction and educational and professional level, this software would seem more practical.

The homepage for FluentU documents what they view to be their selling points: “access to the web’s best foreign language content”; “understand and truly enjoy real world videos”; “learn words from real world context.” FluentU claims to give “students quality independent practice and offers valuable exposure in a way that is fun and appealing, yet effective.” These selling points are vague, however, as “real world” is never defined. It’s also unclear how this program is “fun and appealing,” though it could be argued that the activity of watching videos is entertaining—until the user becomes bored. Learning does not have to be fun, of course, but using such word choice is likely a persuasive tactic; when consumers spend money for a product, they may feel as though they’re getting more for their money if the product is practical and enjoyable. It’s also unclear how watching videos is an effective means of learning. This program does not include a curriculum that advances learners through levels nor does it provide opportunities for speaking or writing. The program does provide quizzes that check for comprehension, but this option is only available if the user purchases the more expensive Plus plan, and these quizzes do not ask open-ended questions that allow the learner to apply language concepts.

FluentFlix links several reviews of their software on the site. These reviews were produced by bloggers and are all highly positive. This in and of itself is not concerning—I would not expect FluentFlix to publicize negative reviews. However, the comments on the blogs from individuals who are supposedly not associated with FluentFlix are also overwhelmingly enthusiastic and willing to try the software:

It’s concerning that each of the comments were posted on the same day within minutes of each other and almost immediately moderated. Most blogs do not experience such a high traffic and response volume. This suggests that the comments and/or the commenters are not authentic. Such sketchy behavior may cause users to hesitate in sharing their credit card numbers for use of this site.

The cost of the software also limits user access. In order to fully experience the software, a user would have to pay $30 for one month of access. A cheaper rate is available, but the user must commit to using the program for 12 months in order to take advantage of the cheaper rate. This is a significant commitment a user must make based on a brief, 15-day trial period. FluentFlix may argue that a 15-day free trial is ample time for a user to determine if the program would suit his or her learning needs, but it is unethical to ask for a payment method for an item that a consumer has not yet committed to buy, which FluentFlix does.

And finally, because this program can only be accessed online, users who do not have a full-time or reliable internet connection would not be able to fully experience this product, nor would they have the same uninhibited access as users with reliable internet.

and are a response to the progressive education that emerged from an industrialized society. We were able to gather this understanding from the readings we did in McComsky and Lauer, where we discussed the building pressure between the increased specialization of knowledge and professional work that was needed. Pressure still exists, but a different kind, and as I consider my role in the WAC field, it will be very important for me to emphasize the need for cultivating students to become effective citizens to alleviate the pressure of an unpredictable economy as well as unpredictable global tensions. Part of this involves developing curriculum that enables students to communicate effectively in both written and verbal contexts, but part of this also involves

and are a response to the progressive education that emerged from an industrialized society. We were able to gather this understanding from the readings we did in McComsky and Lauer, where we discussed the building pressure between the increased specialization of knowledge and professional work that was needed. Pressure still exists, but a different kind, and as I consider my role in the WAC field, it will be very important for me to emphasize the need for cultivating students to become effective citizens to alleviate the pressure of an unpredictable economy as well as unpredictable global tensions. Part of this involves developing curriculum that enables students to communicate effectively in both written and verbal contexts, but part of this also involves

current president-elect will continue to do so long after inauguration day in January. The debates in the field of English over foundations, theories, practices, and approaches likewise carry on. And, like politics, our English-related debates have developed over decades and continue to persist. Literary studies, for example, oppresses composition with its humanist approach to pedagogy, thereby deeming literary studies as superior and composition as “a barely tolerated stepchild (cited in Gaillet, p. 164). Tensions persist, but in the midst of them, we—

current president-elect will continue to do so long after inauguration day in January. The debates in the field of English over foundations, theories, practices, and approaches likewise carry on. And, like politics, our English-related debates have developed over decades and continue to persist. Literary studies, for example, oppresses composition with its humanist approach to pedagogy, thereby deeming literary studies as superior and composition as “a barely tolerated stepchild (cited in Gaillet, p. 164). Tensions persist, but in the midst of them, we—

instructional strategies to further support transfer (e.g. student understanding of context in classes outside of and beyond FYC). These benefits, however, can only achieve their potential through communication and cooperation across the disciplines. So with such potential benefits that could result from WAC, I can’t help but wonder why the disciplines remain divided. Why do we resist each other? Or better yet, why do other fields (English and non-English) continue to resist composition? It’s ironic to me that the university often prides itself in its interdisciplinarity, but when it comes to reaching across the aisle to a different discipline, power often takes priority over cooperation.

instructional strategies to further support transfer (e.g. student understanding of context in classes outside of and beyond FYC). These benefits, however, can only achieve their potential through communication and cooperation across the disciplines. So with such potential benefits that could result from WAC, I can’t help but wonder why the disciplines remain divided. Why do we resist each other? Or better yet, why do other fields (English and non-English) continue to resist composition? It’s ironic to me that the university often prides itself in its interdisciplinarity, but when it comes to reaching across the aisle to a different discipline, power often takes priority over cooperation. While over 200,000 American troops were fighting abroad in the Vietnam War by the 1970s, American education at home was taking a shift toward science, technology, engineering, and math studies (STEM) in order to better prepare a workforce for post-industrial society. Writing education, as a result, also shifted, seeking to identify pedagogical approaches for getting students to think about the content in their various courses and the interrelatedness of writing between them. According to Kevin Eric DePew, Associate Professor of English at Old Dominion University, Writing Across the Curriculum (WAC) emerged as a product of the 70s and a response to this writing studies need: “Though they weren’t using the acronym STEM yet, you had the sense of making everything very STEM-like, or practical, including writing” (personal communication, October 26, 2016). In a post-industrial society in which services were dependent upon intelligent designers and users of technology, practicality in writing meant that the consumers, or students, would be able to see the usefulness and transferability of their writing skills across contexts.

While over 200,000 American troops were fighting abroad in the Vietnam War by the 1970s, American education at home was taking a shift toward science, technology, engineering, and math studies (STEM) in order to better prepare a workforce for post-industrial society. Writing education, as a result, also shifted, seeking to identify pedagogical approaches for getting students to think about the content in their various courses and the interrelatedness of writing between them. According to Kevin Eric DePew, Associate Professor of English at Old Dominion University, Writing Across the Curriculum (WAC) emerged as a product of the 70s and a response to this writing studies need: “Though they weren’t using the acronym STEM yet, you had the sense of making everything very STEM-like, or practical, including writing” (personal communication, October 26, 2016). In a post-industrial society in which services were dependent upon intelligent designers and users of technology, practicality in writing meant that the consumers, or students, would be able to see the usefulness and transferability of their writing skills across contexts.

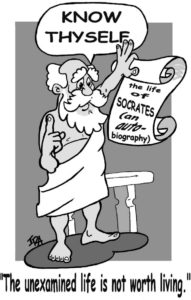

represented in WAC is rhetorical theory, which Bazerman and Russell (1994) discuss in their introduction to Landmark Essays. WAC was evident in the rhetorical traditions of the Ancient Greeks as it is today, and for Bazermen and Russell, there is a long tradition in rhetorical theory to support the reasons we have WAC.

represented in WAC is rhetorical theory, which Bazerman and Russell (1994) discuss in their introduction to Landmark Essays. WAC was evident in the rhetorical traditions of the Ancient Greeks as it is today, and for Bazermen and Russell, there is a long tradition in rhetorical theory to support the reasons we have WAC. Holmes draws on Susan Wells to justify her support of the archive, and reminds us that we are no longer limited to traditional archival work due to recent technological advancements; searchable and generative databases should be considered archives. According to Wells, archival work “help[s] us to rethink our political and institutional situation,” thus allowing us to reconfigure “how we situate and represent our larger scholarly conversation and practices” (cited in Holmes, p. 77). Archival work, therefore, allows us to discover the definition of WAC and the methodologies we use to implement and assess WAC in spite of what our current situation is or is not.

Holmes draws on Susan Wells to justify her support of the archive, and reminds us that we are no longer limited to traditional archival work due to recent technological advancements; searchable and generative databases should be considered archives. According to Wells, archival work “help[s] us to rethink our political and institutional situation,” thus allowing us to reconfigure “how we situate and represent our larger scholarly conversation and practices” (cited in Holmes, p. 77). Archival work, therefore, allows us to discover the definition of WAC and the methodologies we use to implement and assess WAC in spite of what our current situation is or is not.

case, then the field will continue to struggle to define itself as long as there are questions about methodology. So at what point do definition of a field and methodology depart from each other? Are the terms inseparable? Must our methodology be driven by the conventions of our field alone and vice versa? Given these questions after thirt-plus years of WAC research, we seem to still be at commencement.

case, then the field will continue to struggle to define itself as long as there are questions about methodology. So at what point do definition of a field and methodology depart from each other? Are the terms inseparable? Must our methodology be driven by the conventions of our field alone and vice versa? Given these questions after thirt-plus years of WAC research, we seem to still be at commencement.

apprehensions about being called “professor” were affirmed when I was tasked with this blog post, and I began to realize the challenge—and value—in being able to articulate how I align myself theoretically and epistemologically. What theories frame my pursuit of knowledge? What are my beliefs about discovering knowledge about my field? Perhaps I have struggled to embrace my position as an educator because I had not before defined myself in these terms, and in doing so, I had not before claimed a position as a scholar in my field or in academia.

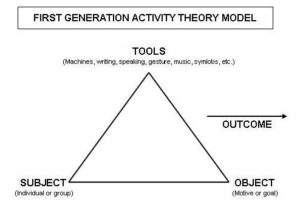

apprehensions about being called “professor” were affirmed when I was tasked with this blog post, and I began to realize the challenge—and value—in being able to articulate how I align myself theoretically and epistemologically. What theories frame my pursuit of knowledge? What are my beliefs about discovering knowledge about my field? Perhaps I have struggled to embrace my position as an educator because I had not before defined myself in these terms, and in doing so, I had not before claimed a position as a scholar in my field or in academia. ial opportunities, enable us to use our higher level thoughts in conjunction with our surrounding environments that are working to shape our knowledge and in turn shape our output (e.g. verbal and written speech) (Brufee) (Hewett and Ehmann, 2004, pp. 34-37). Social constructivism allows me to make the teaching and learning experience transparent, which is essential to successful transfer as students leave my English classroom and enter into classrooms of other disciplines.

ial opportunities, enable us to use our higher level thoughts in conjunction with our surrounding environments that are working to shape our knowledge and in turn shape our output (e.g. verbal and written speech) (Brufee) (Hewett and Ehmann, 2004, pp. 34-37). Social constructivism allows me to make the teaching and learning experience transparent, which is essential to successful transfer as students leave my English classroom and enter into classrooms of other disciplines.